Major

(Honorary

Lieutenant Colonel)

JAMES

PATRICK HAUGH

Royal

Engineers

by

Lieutenant Colonel (Retired)

Edward De Santis, MSCE, PE, MinstRE

(U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers)

(March 2023)

PROLOGUE

This research was prompted by the acquisition of a postcard photograph of James Patrick Haugh that was produced at the time of the Great War of 1914-1918. The back of the postcard is very neatly inscribed in ink, no doubt indicating the identity of the man in the photo.

“Very sincerely yours,

James P. Haugh

Brecon Jan 1915”

Figure 1. Sergeant James

Patrick Haugh, Royal Engineers

(Image from the author’s

collection)

When I first saw the photograph my initial reaction was that I was looking at one of the “sharpest” non-commissioned officers of the Royal Engineers, perhaps even in the Army. As I got into researching his story I soon learned that he actually rose to the rank of Major and retired with the rank of Honorary Lieutenant Colonel.

1. INTRODUCTION

The principal references used in the preparation of this narrative were from a number of sources. They include census records, official registries in the United Kingdom, a family tree on Ancestry.com, Army Lists, and The London Gazette. All sources are contained in the REFERENCE section at the end of the narrative and are cited throughout in the ENDNOTES. Every effort has been made to accurately portray the life and military service of Lieutenant Colonel Haugh.

Family Information

James Patrick Haugh was the son of William John Haugh (1853-1939), a supervisor of Inland Revenue, and Mary Haugh (1882-1948) (maiden name unknown). James came from a large family consisting of four siblings and eleven half-siblings, according to the Reilly family tree (preilly328) found on Ancestry.com. It would appear that Mary was the second wife of William John Haugh. She was 29 years his junior and through the combination of his two marriages they raised 16 children. James’s siblings and half-siblings will be discussed later in this narrative.

Early Life

James Patrick Haugh was born on 15 February 1890 in England, probably in Derbyshire. He attended Chesterfield Grammar School.

Figure 2. Chesterfield Grammar

School.

(Image courtesy of Pictures of the Past)

Haugh appears to have continued his education in a university and obtained a degree in Civil Engineering. After becoming a civil engineer or perhaps while attending university, he worked as an assistant in the Chesterfield Borough Surveyor’s Office under Mr. Vincent Smith and after receiving his degree he became the Chief Assistant Surveyor to the Pontypridd (South Wales) Council.[1]

|

Figure 3. James Patrick Haugh as a Young Man. This image of James Haugh was probably made while he was a student or a young surveyor working in the office of the Chesterfield Borough Surveyor. Note the remarkable difference in his appearance from that in Figure 1, where as a Sergeant in the Royal Engineers he exudes extreme confidence and discipline.

|

Undoubtedly he aspired to continue working in his chosen profession when in 1914 the Great War put a temporary end to his ambitions. With a desire to serve and with his credentials as a surveyor and a civil engineer, he was prompted to enlist in the Corps of Royal Engineers to assist the war effort. This he did, probably in the autumn of 1914.

3. ENLISTMENT AND COMMISSIONING

Enlistment

Haugh enlisted in the Glamorgan (Fortress) Engineers, R.E. as a Sapper, maybe as early as August of 1914 at Cardiff. His selection of this unit into which enlist was probably the result of his working in South Wales for the Pontypridd Council when the war broke out. The Glamorgan Fortress Royal Engineers was first raised in 1885 as a Volunteer unit of Submarine Miners to defend the Severn Estuary. When the Volunteers were subsumed into the new Territorial Force (TF) in 1908, most of the unit formed the Glamorgan Fortress Royal Engineers, but the early interest of the unit in signalling led to the simultaneous creation of the Welsh Divisional Telegraph Company, RE, with an initial strength of 44, which was the first TF telegraph unit recognized by the War Office in 1908. Both units had their headquarters at The Drill Hall, Park Street, Cardiff. While the telegraph (later signal) company was assigned to the TF's Welsh Division, the fortress engineers formed part of Western Coast Defences, with the following organization:[2]

No. 1 Works Company at Park Street in Cardiff.

No. 2 Works Company at the Drill Hall, Gladstone Road, Barry in the Vale of Glamorgan.

No. 3 Electric Lights Company at Park Street (operating coast defence searchlights)

Given Haugh’s skill as a civil engineer, it is most likely that he was posted to one of the Works Companies. His skills also were quickly recognized by his commanding officer, as he was promoted to Corporal within two months of joining the unit and to Sergeant in three months.[3]

As a non-commissioned officer he was appointed a Military Foreman of Works and was sent to Brecon, the headquarters of the South Wales Borderers, to superintend the erection of military huts and laying out of the camp for the regiment. Following this assignment he returned to his company at Scoveston Camp, near Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire and then was transferred to Fort Scoveston.[4] The fort was designed as a garrison for 128 men, and was designed to have a complement of 32 guns. Cost and the declining requirement for forts in the twentieth century meant that guns were never installed. It was never garrisoned, and was used mainly as a training camp for volunteers and militia. World War I saw increased activity in the fort. In order to protect the dockyards of Milford Haven, Neyland and Pembroke Dock, a complex system of trenches was built in the land surrounding the fort to ward against land based attack. The trench system ran from Waterston to Llangwm. Haugh’s company may have used the fort for a time for training purposes and may also have been involved with the construction of the trenches mentioned above.[5]

Sergeant Haugh next was assigned as an instructor in miliary engineering to a class of officers from various infantry regiments. Having demonstrated exceptional talent in this area he was promoted to the rank of Quartermaster Sergeant.[6]

Commissioning

On 15 May 1915 Quartermaster Sergeant James Patrick Haugh was appointed a Temporary 2nd Lieutenant in The Welsh Regiment,[7] Army Number 25308. His leadership potential obviously had been seen by someone in authority and he was recommended for a commission. As the Glamorgan Fortress Engineers probably had no vacancy for a new lieutenant, Haugh was commissioned in the 12th (Reserve) Battalion of The Welsh Regiment.[8]

4. GREAT WAR POSTINGS AND CAMPAIGN SERVICE

Wales (1915-1916)

Formed in Cardiff on 23 October 1914 as a Service battalion, the 12th Battalion came under orders of 104th Brigade in the original 35th Division. On 10 April 1915 it became a Reserve Battalion at Kinmel Park and on 1 September 1916 it was converted into the 58th Training Reserve Battalion of 13th Reserve Brigade and lost its connection to The Welsh Regiment. Since Haugh was posted to the 12th Battalion just about three weeks after it was formed, it is likely that he served with it at Kinmel Park.

Kinmel Camp was built in 1915 as a military training camp. The camp was built in a valley between two hills, Engine Hill and Primrose Hill south of the village of Bodelwyddan. The site was largely empty prior to the camp's construction with the only manmade structures in close proximity being abandoned mining buildings. At the time of its construction, it was the largest army camp in Wales.[9]

Second Lieutenant Haugh served in The Welsh Regiment for 9 months and 15 days, from 15 May 1915 to 29 February 1916. It is likely that in addition to his regimental duties he may have been used as an instructor of military engineering for the officers of the regiment. However, at some point it was realized that the posting of a skilled civil engineer and surveyor to a Service Battalion of an infantry regiment, probably was not the best use of resources. Consequently, on 29 February 1916 Haugh returned to the Corps of Royal Engineers, specifically the Welsh Divisional Engineers, as a Temporary Second Lieutenant with his date of rank remaining as 15 May 1915.

On 1 June 1916 Haugh was appointed to the rank of Temporary Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers Territorial Force.[10] On 18 June 1916 his posting to the Welsh Divisional Engineers was announced.[11] Now during the Great War there were three Welsh Divisions, the 38th (Welsh) Division, the 53rd (Welsh) Division and the 68th (2nd Welsh) Division. The 53rd Division served at Gallipoli, Egypt, and Palestine and the 68th Division served on home defense. The 38th Division served in France and Flanders.[12] Since Haugh’s Medal Index Card indicates that he served in France, he would have to have been with the 38th Division for his service in the war. The following is a summary of the 38th Division’s service during the entire war, from its deployment to France in 1915 to its demobilization in 1919. This summary will be followed by a breakdown of the division’s actions during the time that Haugh was serving in the unit.

The 38th (Welsh) Division was raised as the 43rd Division of Herbert Kitchener's New Army, and was originally intended to form part of a 50,000-strong Welsh Army Corps that had been championed by David Lloyd George: however, the assignment of Welsh recruits to other formations meant that this concept was never realized. The 43rd was renamed the 38th (Welsh) Division on 29 April 1915, and shipped to France later that year. It arrived in France with a poor reputation, seen as a political formation that was ill-trained and poorly led. The division's baptism by fire came in the first days of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, where it captured Mametz Wood at the loss of nearly 4,000 men. This strongly held German position needed to be secured in order to facilitate the next phase of the Somme offensive, the Battle of Bazentin Ridge. Despite securing its objective, the division's reputation was adversely affected by miscommunication among senior officers.

A year later the division made a successful attack in the Battle of Pilckem Ridge, the opening of the Third Battle of Ypres. This action redeemed the division in the eyes of the upper hierarchy of the British military. In 1918, during the German spring offensive and the subsequent Allied Hundred Days Offensive, the division attacked several fortified German positions. It crossed the Ancre River, broke through the Hindenburg Line and German positions on the River Selle, ended the war on the Belgian frontier, and was considered one of the Army's elite units. The division was not chosen to be part of the Occupation of the Rhineland after the war, and was demobilised over several months. It ceased to exist by March 1919.

The 38th (Welsh) Divisional Engineers consisted of the following units:

· 123rd Field Company (joined the division in April 1915)

· 124th Field Company (joined the division in April 1915)

· 151st Field Company (joined the division in August 1915)

· 38th Divisional Signal Company

France and Flanders (1917-1918)

While the specific unit to which Haugh was posted is not known, each of the units listed above took part in the same battles and campaigns in France and Flanders, so it may be assumed that Haugh took part in all if not most of them following his arrival in France. He may have missed some of the battles if he was on leave when they took place or if he was convalescing from the wound that he received at Ypres.

Temporary Lieutenant Haugh embarked for France on 8 June 1917 and arrived there on 10 June 1917.[13] On 1 July he was promoted to Lieutenant. His unit took part in the following actions after his arrival:[14]

· Battle of Pilckem: (* (31 July to 2 August 1917)

· Battle of Langemarck: (16 to 18 August 1917)

· Battle of Ancre: (5 April 1918)

His obituary indicates that he was wounded at Ypres.(*) The battle at Pilckem (the Third Battle of Ypres) is the closest that the 38th (Welsh) Division came to Ypres during this time period, so it is assumed that this may have been when he was wounded.

Lieutenant Haugh had been appointed Acting Captain on 7 August 1917, perhaps to fill the position of a section commander in one of the field companies who had been wounded at Pilckem. Following the battle at Ancre, the 38th (Welsh) Division was taken out of the line

His unit took part in the following actions after this appointment:

· Battle of Albert: (21 to 23 August 1918)

· Battle of Bapaume: (31 August to 3 September 1918)

· Battle of Havrincourt: (12 September 1918)

· Battle of Epehy: (18 September 1918)

After the Battle at Epehy, on 24 September 1918, Haugh relinquished his rank of Acting Captain, probably as a result of officer replacements being assigned to his unit.[15] Then as a Lieutenant again he took part in the following actions:

· Battle of the St. Quentin Canal (29 September to 2 October 1918)

· Battle of Beaurevoir: (3 to 5 October 1918)

· Battle of Cambrai: (8 to 9 October 1918)

· Battle of the Selle: (17 to 25 October 1918)

· Battle of the Sambre: (4 November 1918)

At some point near the end of the war Haugh was again appointed Acting Captain. According to the War Services Army List of 1924 he departed France on 11 November 1918, the day that the war ended. Since the division was demobilized over several months when the war ended, it is unlikely that he retired to England on 11 November since he was a late arrival to the war zone and priority would have been given to officers who arrived in France soon after the division was deployed. He may have been appointed an Acting Captain again as a “stay behind” officer so that he could assist the demobilization of men and equipment from France back to the U.K.

5. POST SERVICE LIFE (1918-1939)

Upon his return to the U.K. he took up residence in 1919 at 19 Ralph Street in Pontypridd, Wales. At some point during 1919 he also lived in Lan Park in Pontypridd in a house called “The Mount.” He probably had returned to Pontypridd to take up his old position with the Council as a Surveyor.

Figure

4. 19 Ralph Street, Pontypridd, Wales.

(Image courtesy of

Google Earth)

On 30 March 1919 he relinquished the rank of Acting Captain, having successfully performed all his assigned duties related to the demobilization of the engineer units of the 38th (Welsh) Division, when the division ceased to exist.[16]

On 1 July 1920 Haugh was promoted to Captain in the Royal Engineers Territorial Army and was posted to the 53rd (Welsh) Divisional Engineers with the unit’s drill hall in Swansea.[17] At this point he probably was serving with the Reserve of Officers.

|

Figure 5. The Haugh

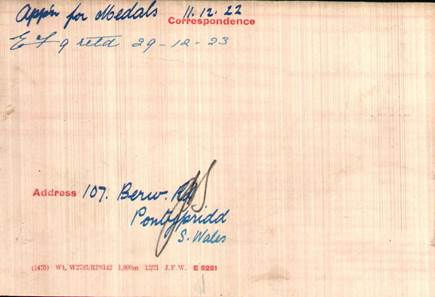

Residence at 107 Berw Road in Pontypridd, Wales. Haugh married sometime prior to the autumn of 1921. His wife’s name appears for the first time living with him in the Pontypridd Electoral Register of Autumn 1921. From 1922 to 1925 he and his wife lived at 107 Berw Road in Pontypridd. |

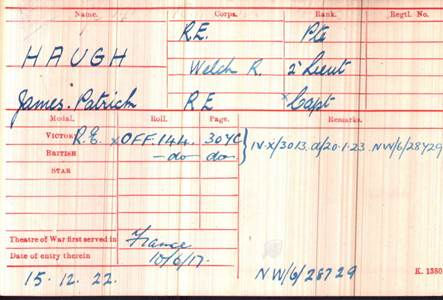

Haugh’s Medal Index Card indicates that he applied for his medals from the Great War on 11 December 1922 and the card shows his entitlement to the British War Medal and Victory Medal.[18]

Figure

6. Medal Index Card (front)

(Image courtesy of

Ancestry.com)

Figure

7. Medal Index Card (back)

(Image courtesy of

Ancestry.com)

The medals were issued to Haugh on 15 December 1922.

Figure 8. The Great War

Medals of the Kind Issued to Haugh.

(Image from the author’s

collection)

NOTE: These are not Haugh’s actual medals. The whereabouts of his medals are unknown to the author.

On 1 March 1923 Haugh was appointed to the rank of Major (Provisional) and was confirmed in the rank in the 53rd (Welsh) Divisional Engineers.[19]

From 1925 to 1926 the Haughs resided at 9 Ceridwen Terrace in Pontypridd.[20]

|

Figure 9. The Haugh

Residence at 9 Ceridwen Terrace in Pontypridd. It may be assumed that after his demobilization from the Army he began to practice in his technical fields of surveyor and civil engineer. His experience as a Foreman of Works in the Army added a new field for him, that of engineering manager. While engaged in the practice of engineering in civil life, he continued to serve in the Reserve of Officers.

|

On 28 July 1926 Haugh was confirmed in the rank of Major, no longer Provisional, in the 53rd (Welsh) Divisional Engineers.[21] At some time in 1926 the Haughs moved from Pontypridd to Kettering, Northamptonshire. In Kettering he was appointed as the Deputy Engineer of the town. Among the many projects that he oversaw in this position, he:[22]

· worked on the reconstruction of the town’s footpaths and streets and improved street lighting,

· started controlled tipping and instituted the laying of 6-inch water mains to factories in the town, thereby improving fire-fighting capabilities,

· supervised the re-building of Kettering’s outdoor swimming bath,

· supervised the building of Kettering’s Crematorium, and

· supervised the construction of thousands of the town’s council houses.

He did all this work while he continued to serve in the Reserve of Officers of the Royal Engineers. On 15 August 1939 he reached the age limit for continued military service and he was retired in the rank of Major with permission to wear the prescribed uniform as needed.[23] However, the start of another World War brought him almost immediately back into military service.

6. SERVICE IN WORLD WAR 2

Deputy Chief Engineer, London (1939-1941)

On 28 November 1939 the London Gazette notice that had him retiring from the Army was rescinded and he was appointed the Deputy Chief Engineer in the London Division with the temporary rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His first duty assignment involved the reconstruction of bomb-damaged public services in the city.[24] Apparently his age was no longer a reason to prevent him from serving, as his skills were required by the Army for this special assignment.

Haugh’s cousin wrote to a publication in Kettering known as The Universe, telling the editor that Haugh was engaged in “the dangerous work . . . supervising and directing the Engineers to remove the fuses from unexploded bombs and mines and also delayed action bombs dropped on London.” The Universe published the following on 11 June 1943 in a section of the publication entitled ‘Heroes Corner:”

Lt.-Col. J.F. Haugh, R.E., Kettering’s peace-time surveyor, recalled to the Army at the outbreak of war, has been awarded the O.B.E. He has been in charge of special R.E. companies engaged on reconstruction, including some highly dangerous work during the raids on London.

Haugh’s cousin and The Universe made it sound like he was engaged in bomb disposal work, where there is no indication in any military records to indicate that this was the case. It appears that after bombs exploded or after the actual bomb disposal teams defused and removed bombs dropped on London, Haugh became involved with the repair of the damage caused by the bombs. A good example of the type of work that Haugh did is described in an article written by him in The Royal Engineers Journal of September 1941. In that article, entitled LONDON’S LARGEST CRATER, he describes the repair of a large crater in the center of the open space at the junction of Lombard Street, King William Street, Queen Victoria Street, Princes Street, Poultry, Threadneedle Street and Cornhill. The crater was 1,800 square feet in area, 150 feet long and from 10 feet to 30 feet deep. Haugh’s job was the elimination of this crater using General Construction Company resources of the Royal Engineers. When he wrote this article he used the postnominals F.S.I. (Fellow of the Chartered Surveyor Institution) and M.I.M.&CY.E (a postnominal of unknown meaning).

Commander Royal Engineers, Bicester (1941-1945)

In the autumn of 1941 Haugh was appointed a special Commander Royal Engineers (C.R.E.) for the construction of a huge central ordnance depot at Bicester, Oxfordshire, with an estimated cost of £5 million. The depot was to form the main post-war ordnance depot. Work force consisted of a large civil labour force, artisan works companies, pioneers and 1,000 Italian prisoners of war. The depot was to consist of 6¾ million square feet of covered storage, mostly steel framework with brick cladding and 5 million square feet of open storage space, accommodation, with all necessary amenities for 14,000 personnel. There were to be 60 miles of railway and 24 miles of roads and extensive drainage was necessary in many parts of the area. As work progressed, the original cost estimate was increased to £6¼. The depot was not completed by the end of the war.[25]

General List (1945-1946)

In the Royal Engineers List of 1943 Haugh is listed in the Royal Engineers Territorial Army Reserve of Officers (General List). On 2 June 1943 he is shown in the London Gazette as Major (temporary Lieutenant Colonel), 23508 Royal Engineers, awarded the O.B.E, Military for his work on bomb-damage repair in London. Haugh was still serving as a Major in 1945, but on 29 March 1946 he relinquished his commission after having exceeded the age limit for further service and was granted the honorary rank of Lieutenant Colonel.[26]

7. RELEASE FROM SERVICE

Major (Honorary Lieutenant Colonel James Patrick Haugh) was released from service (the Reserve of Officers) on the 29th of March 1946, having attained the age for continued service. His total service was reckoned as shown in the tables below:

Location |

|

Cardiff, Wales (Royal Engineers) |

15 August 1914[27] – 14 May 1915 |

Cardiff, Wales (The Welsh Regiment) |

15 May 1915 -28 February 1916 |

Wales (Welsh Divisional Engineers) |

1 March 1916 – 7 June 1917 |

France and Flanders |

8 June 1917 – 11 November 1918 |

Swansea, Wales |

12 November 1918 – 30 March 1919 |

Reserve of Officers (Wales) |

31 March 1919 – 28 November 1939 |

London |

29 November 1939 – 15 September 1941[28] |

Bicester, Oxfordshire |

16 September 1941 – 29 March 1946 |

Location |

|

Home Service |

9 years, 1 month and 19 days |

Service Abroad |

1 year, 5 months and 4 days |

Total Service (Active) |

10 years, 6 months and 23 days |

Total Service (Reserve) |

20 years, 7 months and 29 days |

Total Service |

31 years, 2 months and 22 days |

8. POST SERVICE LIFE

Upon leaving the Army he took up residence at 4 Westleigh Road, Barton Seagrave, Kettering. In 1955 he was elected a member of the Kettering Town Council, running for the office as an Independent Conservative for Barton Ward.[29]

Figure

10. The Haugh Home at 4 Westleigh Road in Kettering.

(Image

courtesy of Google Earth)

After his compulsory retirement from the town council at the age of 65, there was quite a bit of controversy in the council at the time. Hough decided to stand for the council again as an independent candidate and he regained the seat by 508 votes over the Labour nominee.

In 1956 Haugh and his wife left Kettering for full retirement in Exmouth, Devonshire. He died there on 8 July 1960 at North Lodge, Courtlands, Exmouth at the age of 70. Present at his funeral were his wife, Dorothy Haugh, and his two children, James (“Jack”) Haugh and Mrs. Jill Armstrong his daughter.[30] Also present were his five grandchildren.[31]

Figure

11. James Patrick Haugh in Later Years.

(Image

courtesy of the Reilly family tree [preilly328].

The probate of Lieutenant Colonel Haugh’s will took place in Exeter on 2 September 1960 with all his effects going to his wife Dorothy Mary Elizabeth Haugh (1889-1968). His effects amounted to £4,544, 2 shillings and 8 pence, or about $154,400 US in 2022 currency).[32] Dorothy Haugh died in Devon Central, Devonshire in December of 1968.[33]

9. MARRIAGE, FAMILY AND PERSONAL INFORMATION

Spouse and Children

The information regarding his marriage to Dorothy Mary Elizabeth (maiden name unknown) was estimated from the Electoral Registers of Pontypridd as previously indicated. Unfortunately, in all the Haugh family trees found on Ancestry.com, her maiden name is not given. Scant information is provided in a family tree regarding the names of their children and in the probate calendar as indicated above.

Parents

Very little dependable information is provided about James Patrick Haugh’s parents in the family trees presented on Ancestry.com. His father, William John Haugh, may have been born in Ireland in 1853 and died in 1939. His mother Mary Haugh (maiden name unknown) was born in 1882 and died in 1948. If these birth dates are accurate, then his father was 29 years older than his mother. As previously indicated, James had four true siblings and 11 half-siblings. The family trees show all the half-siblings with the name of Haugh, so they must have been the children of William Haugh and his first wife (name unknown).

Siblings and Half-Siblings

Since so little is known about Haugh’s siblings and half-siblings, only their names and year of birth will be listed, as they were found on the Reilly family tree (preilly328) on Ancestry.com.

True Siblings (father William John Haugh, mother Mary Haugh)

Willie Haugh, 1882.

Bridgit Haugh, 1888.

Thomas Haugh, 1891.

Half-Siblings (father William John Haugh, mother unknown)

Robert John Haugh, 1880.

Mary Jane Haugh, 1881.

Anna Eliza Haugh, 1883.

Thomas Haugh, 1884.

Sarah Haugh, 1886.

William Francis Haugh, 1888.

Samuel David Haugh, 1894.

John Haugh, birth date unknown, year of death 1937.

William Haugh.

Winnie Haugh.

Ellie Haugh.

The accuracy of the family tree information is questionable. An examination of the years of birth of the half-siblings indicates that some of them were born between two of the siblings. Either the half-siblings were not the children of William John and Mary Haugh, or William John Haugh was a bigamist and had two families. Another possibility is that he adopted the half-siblings and gave them his name. The fact that two of the half-sibling boys were named William is another oddity. William Francis Haugh (1888) may have died as an infant and William John Haugh and his wife decided to name a second child William. There are many possibilities to explain the discrepancies with the names of the children and their dates of birth. The most likely explanation is that the family tree contains individuals who were not in the family of William John Haugh.

REFERENCES

Army Lists

Monthly Army List, December 1917, p. 831c.

Monthly Army List, December 1918, p. 831c.

Monthly Army List, December 1920, p. 831.

Annual Army List, 1922, p. 840.

Supplement to the Half-Yearly Army List, 31 December 1924, p. 291.

Books

Pakenham-Walsh, R.P. History of the Corps of Royal Engineers, Volume VIII, 1938-1948. The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, 1958.

MUNBY, J.E. (ed.). A History of the 38th (Welsh) Division. Hugh Rees, Ltd., London, 1920.

Census

1901 Census of Ireland.

Documents

UK Probate Calendar, 1960, p. 287.

Handwritten note regarding Haugh’s work during World War 2, undated, signed Herbert.

Extract from THE UNIVERSE of 11 June 1943, entitled “Heroes Corner.”

Obituary, undated, source not known.

Wales Electoral Registers, 1832-1978.

Family Trees (Ancestry.com)

James Patrick Haugh (1890-1960) (Reilly family tree, preilly328).

William Haugh (1853-1939) (father) (Reilly family tree, preilly328)

Internet Web Sites

British Army Records and Lists, 1882-1962

The Long, Long Trail: 53rd (Welsh) Division.

https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/order-of-battle-of-divisions/53rd-welsh-division/

J P Haugh: UK, Military Discharge Indexes, 1920-1971.

Glamorgan Fortress Royal Engineers.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glamorgan_Fortress_Royal_Engineers#Territorial_Force

Fort Scoveston.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scoveston_Fort

The Long, Long Trail: The Welsh Regiment.

Kinmel Park Training Area.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinmel_Park_Training_Area

8. Wikipedia: 38th (Welsh) Infantry Division.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/38th_(Welsh)_Infantry_Division

London Gazette

The London Gazette, 18 May 1915, p. 4782 and 4783.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 28 February 1916, p. 2205.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 17 June 1916, p.6048.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 23 October 1917, p. 10895.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 24 September 1918, p. 11326.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 2 June 1919, p. 6675.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 22 July 1920, p. 7753.

The London Gazette, 1 June 1923, p. 3870.

The London Gazette, 9 October 1925, p. 6506.

The London Gazette, 27 July 1926, p. 4963.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 28 November 1939, p. 8027.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 10 October 1940, p. 5954.

Supplement to the London Gazette, 2 June 1943, pp. 2423 and 2426 (Birthday Honours List).

Supplement to the London Gazette, 29 March 1946, p. 1574.

Military Documents

Medal Index Card (MIC) of Captain James Patrick Haugh, R.E. (WO 372/9/84888).

Royal Engineers Medal Roll: British War Medal and Victory Medal.

Periodicals

The Royal Engineers Journal, September 1941, p. 265. LONDON’S LARGEST CRATER. Lieut.-Col. J.P. Haugh, F.S.I., M.I.M.&CY.E., R.E.

The Royal Engineers List, 1943, p. xxxviii.

The Royal Engineers Journal. The Institution of Royal Engineers, Chatham, Kent, 1925-1932. Battle Honours of the Royal Engineers.

The Derbyshire Courier, 29 May 1915.

ENDNOTES:

[1] The Derbyshire Courier.

[2] Glamorgan Fortress Royal Engineers

[3] Derbyshire Courier.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Fort Scoveston.

[6] The dates of his promotions to various ranks would be available in his military service papers if they still existed at the Army Personnel Centre in Glasgow. No attempt has been made by the author to obtain these papers.

[7] The London Gazette, 18 May 1915.

[8] Derbyshire Courier.

[9] Kinmel Park Training Camp.

[10] Army List, December 1917.

[11] London Gazette, June 1916.

[12] The Long, Long Trail.

[13] War Services Army List and Medal Index Card.

[14] Royal Engineers Journals, 1925-1932.

[15] London Gazette, September 1918.

[16] London Gazette, June 1919.

[17] Monthly Army List, December 1920, Army List 1922 and the London Gazette, July 1920.

[18] The Medal Index Card shows him as a Private in the Royal Engineer prior to his commissioning. The Royal Engineers did not have the rank of Private. He joined the R.E. either as a Sapper or a Pioneer, most likely a Sapper.

[19] London Gazette, June 1953.

[20] Electoral Registers.

[21] London Gazette, 27 July 1926.

[22] Obituary.

[23] London Gazette, November 1939.

[24] London Gazette, October 1940.

[25] R.E. Corps History, Volume VIII.

[26] London Gazette, March 1946.

[27] Approximate date.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Obituary.

[30] Jill was the wife of one Eric Armstrong.

[31] Obituary.

[32] UK Probate Calendar, 1960.

[33] Family tree.